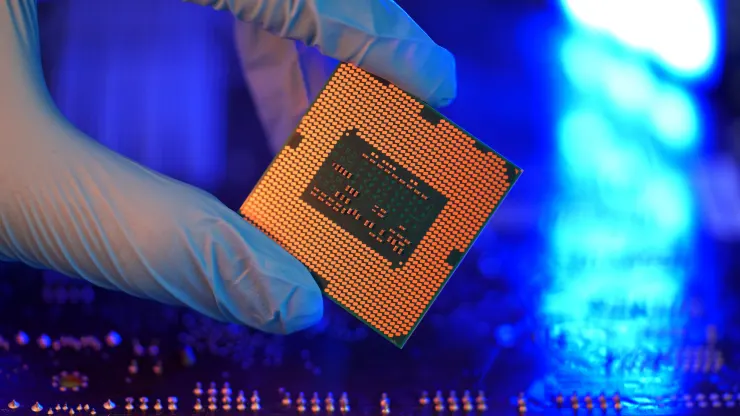

he European Union has agreed a landmark plan to boost its chip industry.

The initiative, dubbed the European Chips Act, seeks to help the bloc compete with the U.S. and Asia on tech, and secure control over a critical bit of technology behind the world’s electronics products and devices.

The EU Parliament and 27 member states reached a deal on the legislation on Tuesday. In a statement, they said the new rules would aim to double the EU’s global market share in semiconductors from 10% to 20% by 2030.

“This agreement is of utmost importance for the green and digital transition while securing the EU’s resilience in turbulent times,” Ebba Busch, the Swedish energy minister, said Tuesday.

“The new rules represent a real revolution for Europe in the key sector of semiconductors.”

What’s in the Chips Act?

The European Chips Act is a massive, 43-billion-euro ($47 billion) package of public and private investments that aims to secure its supply chains, avert shortages of semiconductors in the future, and promote investment into the industry.

The Chips Act has three main aims:

- Building large-scale capacity and innovation.

- Make sure the EU is self-sufficient.

- Prepare the EU for potential future supply crises.

The EU Chips Act will invest 6.2 billion euros to promote industrialization of innovative technologies, establish competence centers for skill development, and ensure access to finance, the European Commission, the EU’s executive arm, said in a statement.

It will also incentivize investments in manufacturing facilities and provide a framework for integrated production facilities and open EU foundries for security of supply.

Member states will also coordinate to monitor supply and forecast any shortages, the commission said. Since first announcing the plan last year, the EU has already attracted between 90 billion and 100 billion euros of public and private commitments for industrial deployment.

Why does it matter?

Chips are effectively the brains of electronic devices. They’re used in everything from smartphones to gaming consoles — but also products you wouldn’t expect them in, like cars and refrigerators.

Semiconductors, and the mainly East Asia-based supply chain behind them, have become a thorny issue for world governments after a global shortage led to supply problems for major automakers and electronics manufacturers.

The Covid-19 pandemic exposed an overreliance on manufacturers from Taiwan and China for semiconductor components. That dependency has become fraught with tensions between China and Taiwan on the rise.

TSMC, the Taiwanese semiconductor giant, is by far the largest producer of microchips. Its chipmaking prowess is the envy of many developed Western nations, which are taking measures to boost domestic production of chips.

Europe has been seeking to control more of its supply chain to reduce its reliance on foreign market players. The move is part of a push from the EU to achieve “digital sovereignty,” which refers to the idea that they have more control over critical technologies.

“A swift implementation of today’s agreement will transform; our dependency into market leadership; our vulnerability into sovereignty; our expenditure into investment,” Busch said. “The Chips act puts Europe in the first line of cutting-edge technologies which are essential for our green and digital transitions.”

Can’t go it alone

At the same time, the bloc has realized it can’t achieve this production ramp up alone — there are no European firms that can manufacture leading-edge chips.

The EU wants to attract funding from foreign companies into its market. U.S. chipmaking giant Intel is among the companies upping its investments in Europe, and has committed over 33 billion euros to boost chipmaking across the EU.

In the U.K., chip firms have been threatening to leave the U.K. due to a lack of similar support from the government.

Europe is home to a titan in the semiconductor space — Dutch firm ASML. ASML’s extreme ultraviolet lithography machines are used to etch microscopic features into silicon wafers. But the company doesn’t produce its own chips.

Officials want more semiconductors to be developed within Europe, so they don’t face the risk of a big shortage, or threats to national security.

Source: CNBCNews