The time is ripe for renewed strategic thinking and leadership on global religious dynamics in U.S. foreign policy.

In 2013, the United States adopted its first ever “National Strategy on Integrating Religious Leader and Faith Community Engagement into U.S. Foreign Policy.” This White House strategy acknowledged the significant contributions of religious leaders and faith communities to human rights, global health and development, and conflict mitigation; and provided an interagency blueprint for integrating more robust engagement with religious actors across a broad range of foreign policy and national security issues. A decade later religious engagement remains a vital but underdeveloped capacity in U.S. foreign policy, and the strategy’s 10th anniversary offers a natural opportunity to revitalize strategic thinking and spur new action on this agenda.

Intended to inaugurate a new portfolio of strategic religious engagement work distinct from (but also complementary to) ongoing efforts to promote international religious freedom, the 2013 National Strategy marked the culmination of a full decade of effort across multiple Republican and Democratic administrations and agencies.

As the only entity within the U.S. national security architecture that has had a programmatic focus on religion almost from the very outset, it was only fitting that USIP convened key figures involved in the creation and implementation of the 2013 strategy to take stock of where we stand in this work. The discussion, which featured contributions from former senior officials, civil society leaders, academic experts and current U.S. government staff, focused on religious engagement and identified a number of key trends and themes related to the future of strategic religious engagement in U.S. foreign policy.

A Different America, A Different World

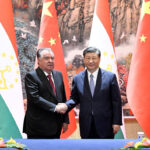

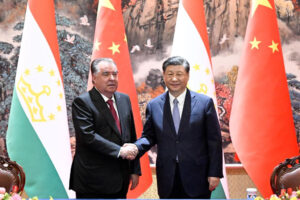

Ten years since the release of the strategy, both the United States and the world more broadly have evolved in significant ways. In the United States, widening domestic political divisions, which involve questions of religion, can complicate how the U.S. approaches religion in its external relations — a theme treated at length in USIP’s 2022 report on the importance of finding common ground in U.S. international religious freedom policy. At the same time, the shape of the global order has been shifting rapidly with a number of key geopolitical players — such as Russia, China, India and Arab Gulf nations —demonstrating a marked tendency to integrate religion into their own foreign policy. The Kremlin’s close partnership with the Russian Orthodox Church in projecting cultural influence into Europe and the Western Balkans, China’s promotion of its Buddhist heritage in various Asian nations, and the United Arab Emirates frequent summits on interfaith tolerance are all relevant examples.

Amid this new landscape, it is vital to maintain synergy between religious engagement work and efforts focused on promoting religious freedom. At the most basic level, some modicum of religious freedom is a prerequisite for carrying out effective religious engagement in any global setting. Furthermore, although faith can be a highly divisive issue, there is a salutary demonstration effect that arises from cooperation across lines of faith in promoting religious freedom. At the heart of this work is the idea that people can and do believe fundamentally different things but can still collaborate effectively to protect their right to do so. This is especially powerful at a time when people who disagree with each other seem increasingly disinclined to reach out across their differences.

Institutionalizing Religious Engagement Capacity and Knowledge

While there has been significant progress on mainstreaming aspects of religious engagement in U.S. diplomacy and development work since 2013, the U.S. government is still struggling with the question of how to effectively institutionalize expertise and capacity relating to strategic religious engagement.

This challenge involves multiple dimensions connected to questions such as where best on an agency organization chart to place an office focused on religious engagement; what expertise on religion should look like in the context of foreign policy and how best to provide it to American diplomats; and how to make sure that senior leaders — ambassadors, mission directors, combatant commanders, even the secretary of state — can recognize the importance of religious engagement and encourage those around them to routinize outreach to and partnerships with faith communities.

Over the last 10 years, we have learned lessons from religious engagement tactics that have proven ineffective. For example, relying primarily on public affairs or strategic communications approaches to religious engagement — rather than tying this work to consistent community engagement around specific policy priorities — heightens the risk that diplomatic overtures in the realm of religion get perceived as rhetoric rather than substantive commitment. To be effective, religious engagement capacity needs to be routinized in day-to-day diplomatic operations, with clear objectives, incentives, accountability and sustainability.

This last point regarding the challenge of durability highlights another obstacle to building effective religious engagement capacity in U.S. diplomacy, one that to some extent is baked into the personnel system that governs careers in the foreign service. Because it can take several years to develop the necessary familiarity and relationships within a given country’s religious landscape, this often means that just as a diplomat has reached a point where she or he is able to undertake effective religious engagement they will often find themselves moving on to a completely new setting and context.

Refreshing the Policy Strategy and Revitalizing Interagency Coordination

When it was first released, the strategy created an important demand signal within the interagency that generated significant momentum — at least for a time. Now we need a refresh.

The strategy served as a mandate not only for U.S. national security and foreign affairs agencies to develop in-house capacity for religious engagement, but also to develop partnerships with civil society for advancing this work. Furthermore, a number of close governmental and intergovernmental partners in other regions and at the multilateral level also began developing an institutionalized focus on religion. For example, several foreign ministries in Europe, as well as the European Union and the United Nations, created envoys, taskforces or offices focused on religious engagement around the same time — and in at least one or two of these cases, we can reasonably point to developments in Washington as an important source of inspiration. Milestone developments such as the 2015 establishment of the Transatlantic Policy Network on Religion & Diplomacy, co-founded by the United States and the European Union, speak to U.S. leadership in this arena. Looking across the full range of U.S. government, intergovernmental and civil society activity in the years following the 2013 National Strategy we can see the clear contours of an emerging ecosystem of religious engagement in diplomacy and development.

While questions such as whether the 2013 strategy should be updated and “reactivated,” or whether we need an entirely new strategy coupled with a new interagency coordination mechanism are clearly up for discussion, there is a clear consensus within the expert community that the time is ripe for renewed strategic thinking and leadership on global religious dynamics in U.S. foreign policy. With religious leaders and faith-based actors increasingly prominent across a wide range of our most pressing global challenges — from the war in Ukraine, to migration and refugees, to climate change — religious engagement needs to become part of the American diplomatic toolkit.

Source: United States Institute of Peace